Today’s blog is written by Christian Gerike: a dream researcher, writer, and teacher who has done dream work for 14 years and is in several dream groups. He taught The Psychology of Dreams at Sonoma State University, California, and for many years facilitated a weekly dream group for the Myth, Dream, Symbol course. Christian believes that “The more that people consciously pay attention to and work with their dreams the better a place the world will be.”

Today’s blog is written by Christian Gerike: a dream researcher, writer, and teacher who has done dream work for 14 years and is in several dream groups. He taught The Psychology of Dreams at Sonoma State University, California, and for many years facilitated a weekly dream group for the Myth, Dream, Symbol course. Christian believes that “The more that people consciously pay attention to and work with their dreams the better a place the world will be.”

You can read more blogs he has written for Mindfunda: Sleep Well, Remembering Dreams and How to Remember your Dreams.

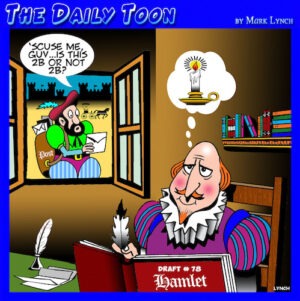

A dream can be analyzed to access information from the unconscious. Dream work, interpreting the manifest dream to understand the latent dream, consists of remembering, recording, and analyzing a dream. Dream work takes into consideration the various elements in a dream, the dream’s setting, the “story” that the dream is telling, the emotions in the dream, and relationships to aspects of one’s life. This is a process of going from the holistic experience of an image to a linear written or spoken description of the image.

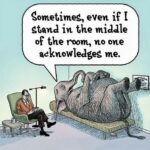

Dream work uses symbolic research and introspection in relation to the dreamer’s personality, emotions, experiences, and culture to arrive at the dream’s meaning. There are many ways that a dream can be interpreted: analyzing the dream’s images for symbolic meanings; treating it as a story; a Gestalt approach views each dream image as an aspect of the dreamer; a dream can be drawn and mapped; and acting out the dream by a group as a form of theater are just a few interpretive techniques. One can interpret a dream by oneself, but generally greater success is achieved by working the dream with a therapist or in a group, as one can be “blind” to aspects of a dream that others readily perceive. (Gerike 2020, p. 20)

Introduction

Group dream work was innovated and popularized by Montague Ullman (Ullman & Zimmerman1979; Ullman 2006) and Jeremy Taylor (1983, 2009) as a way for lay people to work with dreams. Prior to their work, dream work was considered safe only within the context of psychotherapy conducted by a professional. (You can read more about Jeremy Taylor in Mindfunda’s blog about the Trickster.)

Many years and thousands of dream circles later it is obvious that lay group dream work is fun and can help address various personal, societal, and existential concerns that we face in life. But, if someone is having serious problems (e.g., ptsd nightmares) it may be more appropriate for the person to seek help from a therapist who specializes in Jungian psychology or acknowledges dreams, rather than try to resolve it in a dream group setting. Dream circles should never be promoted as, or in place of, therapy. The guidelines below are flexible and can evolve to accommodate the specific situation of a dream group.

A good starting point for doing group dream work is Jeremy Taylor’s Dreamwork Tool Kit: Six Basic Hints for Dreamwork. Taylor touches on dreams as universal language for health and wholeness; the dreamer and the dream’s meaning; dreams have multiple meanings with new information; responding with “in my imagined version’; and confidentiality. The “tool kit” is at http://www.jeremytaylor.com/dream_work/dream_work_toolkit/index.html.

Basic Principles

Conduct all dream work with kindness and respect: keep in mind the concept of “is it true, is it necessary, is it kind?” Always to be considered: is it an improvement over silence?

1) Do not tell someone what their dream means (but, “if it were my dream I would think that . . .” is ok).

2) Do not tell someone what they should do about their dream (but, “if it were my dream I would . . .” is ok).

“If it were my dream” (IIWMD) can be a stealth method of telling someone what their dream means and what to do, so be sure to truly feel into the dream as if it is your dream and take ownership of your views and statements.

Jeremy Taylor, in his later years, changed the IIWMD phrase to “In my imagined version of the dream . . .”. While we cannot possibly experience what the dreamer experienced, we can imagine what that dream may have been like.

Are you experienced

Take the IIWMD concept a bit further and recall your own dream experiences that may be pertinent to the discussion. In other words, it is not “if it were my dream,” but it actually is your dream. If not a dream, another personal experience.

3) Dreamer’s choice. It is the dreamer’s choice to present their dream or a portion of the dream as they choose. It is the dreamer’s choice to answer or not answer questions about the dream. It is the dreamer’s choice to end the dream work for whatever reason they may have: sometimes they are overwhelmed, emotionally upset, or just need space to process what they have learned. Whatever the reason, it is their reason, they do not need to explain why, and the dreamer’s choice is to be honored.

4) Corollary to #3, a dreamer is not asked to do anything they do not want to do. Do not urge someone to answer a question; to undertake a certain activity in response to the dream; or do, say, or think anything they do not want to.

5) Dreams presented in the group should not be discussed with someone outside the group. Private and personal material can come up in a dream presentation and it is inappropriate to share dreams with outsiders.

Group Structure

A dream group generally seems to work best with 4 to 8 people: more is unwieldy; less has insufficient input and diversity.

Consider how the group is to be directed: will there be one person in charge as facilitator, will the facilitator change every meeting on a rotating basis, or . . . ? If someone, for whatever reason, is not comfortable with the role of facilitator, that should be respected.

Decide how often to meet: some groups meet weekly, some every other week, others once a month. A dream group will usually evolve into a small community and it is difficult to maintain cohesiveness if the group does not meet at least once a month.

Bringing someone new to the group can be at the discretion of the person who initially organized the group. The best way, however, is to have consensus. A person uncomfortable with someone else in the group will get in the way of good dream work.

Dream Group Procedures (2-hour meeting)

Presented below is one way of proceeding with a dream group. The procedures will evolve over time and should reflect the desires of the group. Present the dreams in accordance with the time limits. Dream work can go on forever and it may be necessary to arbitrarily end the discussion after about .5 to .75 hour. Then, take a break and on to the next person. A two-hour session usually allows for check-in and working two dreams. By consensus, the dream work time can go over time, or just one dream worked, or a dream is returned to.

Begin: light a candle, then open with a poem, a reading, or play an instrument. Then, have a short meditation, it may just be closing the eyes for a few minutes or it may be a specific guided meditation.

Each person, if they want to, checks in, with a focus on dream experiences/insights/interesting information. As part of the check in present a dream title, a way of everyone participating in the dream work process. At this point, comments by the group, if any, should be kept to a minimum. The dreamer is free to comment on the title and/or the dream, but this is not the time to present nor work a dream.

Decide who will present a dream. If more want to present than time allows, draw names from a hat. At times, someone will ask to present a dream, with an urgent desire to do so. The group generally honors such requests.

Writing up and passing out one’s dream prior to orally presenting is a great way to facilitate the process. The handout can also contain art or anything that inspires a person about the dream. A write-up can make it easier for the dreamer to present and it is an excellent place to take notes of the discussion.

At the beginning of working a dream clarifying questions are often asked: was the dreaming about night or day, what was the color of the car, who is the person that was mentioned, how did you feel emotionally during the dream or upon wakening, etc. This takes place during the beginning of the dream work. Later such questions are generally asked in the IIWMD format, such as: If I were the dreamer, was my path in the dream smooth or muddy?

Comments about the dream are made by the group members on a random basis (popcorn style). There is no requirement to make or not make comments. Possible symbolic meanings of the dream; a myth, poem, or piece of music may come to mind, something current in the news or an historical event that may relate to the dream might come up, the neurological nature of dreaming, the way an animal behaves, and a thousand-and-one various facts, events, and concepts may be mentioned as part of the discussion of the dream. Keep in mind that all comments should be made with kindness and respect.

An awkward situation can arise where one cannot get a word in edgewise into the discussion. One way of dealing with this is by having someone who cannot get in raise their hand.

Towards the end of a presentation the facilitator announces it is time to make final comments (there is some leeway here, but they really should be the last comments everyone makes).

Then, the facilitator asks the dreamer for anything they may have to say, what struck them the most, “ahas” they experienced: any or no observations the dreamer may want to make.

Close: hold hands in a circle (fake it on Zoom), and close the session. The group/facilitator chooses how to proceed; often a closing poem, chant, statement, or observation is made. Take several breathes, three or four, one for the individual, one for the group as a whole, one for the world, and one for any needs (e.g., well-being of animals, someone who may need healing, or just a way of sending good energy into the universe). Blow out the candle.

With today’s ready access to the Internet, it is not unusual for someone to look up a myth, a reference, a poem, a song, or what-have-you while doing dream work. It generally seems to work well and can add understanding to the dream work. Avoid dream dictionaries as dreams are unique to every person; or use several, strictly as stimulation, not answers.

Keeping a dream journal is highly recommended, both as a way of documenting dreams and documenting the dream group experience. This can be a single journal to keep track of all of one’s dream experiences, or separate journals can be kept for one’s dreams and one’s dream work.

There may be email communications after the group meets as people think of something; send a poem, or a myth, or a piece of art, or music, or something they looked up. Consider creating a secret Facebook page where people can post dreams or information and reactions.

Cautions

When presenting a dream, aspects can arise that one did not anticipate and can be embarrassing, personal, or awkward. This is a risk one takes in presenting dreams. There can be disturbing moments where one realizes “I didn’t know that was in the dream.” One just does not know ahead of time what a dream may reveal.

Dream work may bring up deep emotional material. Once the group has been established and people are comfortable with each other, they will generally be willing to go deeper, open up, and be vulnerable. It is not unusual for people to breakdown and cry, or just not be able to continue with working on a dream. They do not need consoling, they need sincere sympathy and respect, often in silence.

Conclusion

Group dream work is fun and interesting while obtaining insights to dreams and learning more about how dreams work and how they can be interpreted. Exploring the wonderous world of dreams through dream groups can result in a better understanding of one’s self, others, and the world.

Bibliography

Castleman, T. (2009). Sacred dream circles: A guide to facilitating Jungian dream groups. Einsiedeln, Switzerland: Daimon Verlag.

Feinberg, D. (1981). Exploring group dream work. Social Work, 26 (6), 509-510.

Gerike, C. (2020). What are those animals doing in our dreams: A review of the literature. Department of Psychology graduate paper. Rohnert Park, CA: Sonoma State University.

Taylor, J. (1983). Dream work: Techniques for discovering the creative power in dreams. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press.

Taylor, J. (2009). The wisdom of your dreams: Using dreams to tap into your unconscious and transform your life. New York, NY: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin.

Ullman, M. (2006). Appreciating dreams: A group approach. New York, NY: Cosimo-on- Demand.

Ullman, M. & Zimmerman, N. (1979). Working with dreams: Self-understanding, problem- solving, and enriched creativity through dream appreciation. Los Angeles, CA: Jeremy P. Tarcher.

Wahl, J.S. (2015). Discover the messages in your dreams with the Ullman method. Dream Digging Guide 1. Albuquerque, NM: MindBalance.

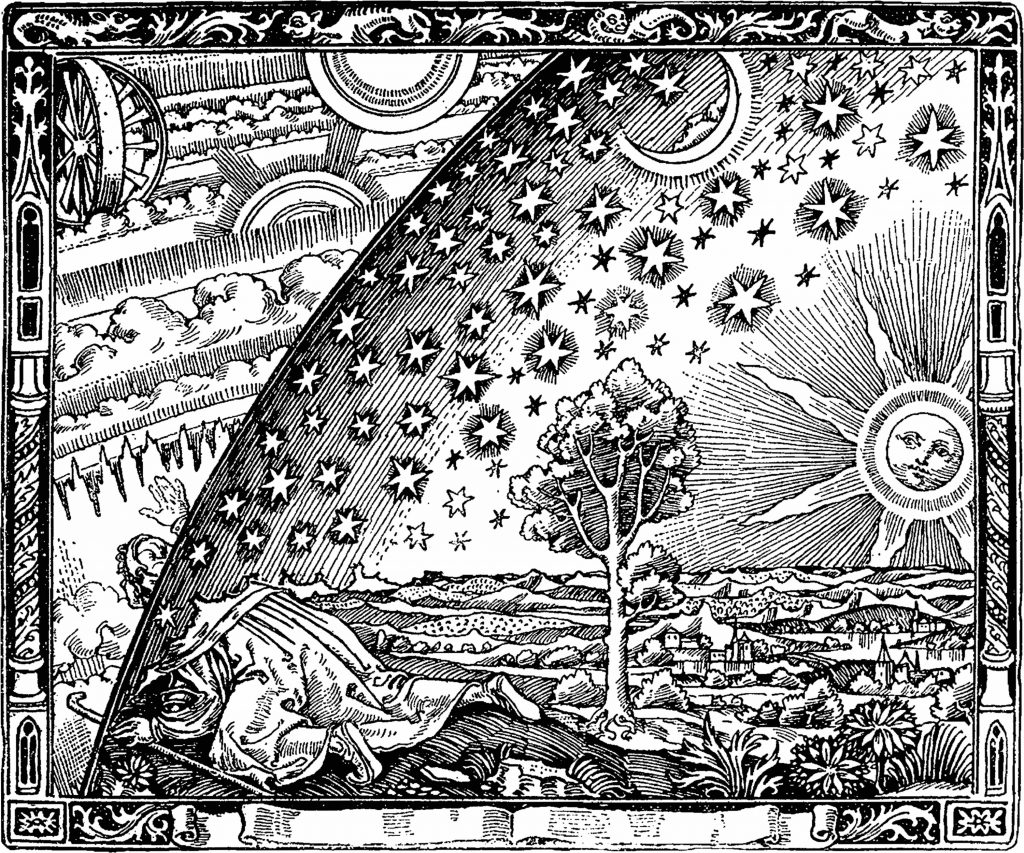

Photo in Header: Faisal Waheed on Unslpash

For our group of seven (often six are able to “attend’) 2 to 2 1/2 hours is enough for check-in and one dream!