Who is Carl Jung?

Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, initially collaborated with Freud (Click to read more) in developing psychoanalysis, a groundbreaking approach at the time. This method introduced techniques such as free association, where patients, often reclining on a couch to feel at ease, would express their thoughts while the analyst explored underlying complexes. However, Jung eventually distanced himself from Freud, primarily due to Freud’s strong emphasis on sexuality as the driving force behind human behavior. Jung, instead, believed in a broader psychological framework, emphasizing the collective unconscious and the role of archetypes, which led him to establish analytical psychology.

Born in 1875 into a religious family—his father was a pastor, and his mother reportedly had spiritual inclinations—Jung grew into a charismatic and articulate figure. He later married Emma Rauschenbach, whom he met when he was 21 and she was 16. While their age difference might raise concerns today, their union was accepted at the time, and Emma became a crucial supporter of Jung’s work.

What Carl Jung book to read first?

Vroom en Dreesmann (often abbreviated as V&D) was a well-known Dutch department store chain, similar to Macy’s in the United States. It was a staple of Dutch shopping streets for over a century, offering everything from clothing and household goods to books and electronics. When I took a walk through Vroom en Dreesmann, I saw the book Man and His Symbols: The Reality of the Unconscious* on display. It was on sale for 19.95—not in euros, but in old Dutch guilders. The book immediately drew me in; I knew I had to have it, that it was important to me. I bought it, and I still have it to this day. From a young age, I wanted to understand the human psyche, and Carl Jung helped me do that through his model of the mind. This is a good beginners book, because often Carl Jung’s writings can be complex, often filled with dense psychological terminology and deep philosophical insights. It introduces key Jungian concepts like archetypes, the collective unconscious, and the process of individuation in a clear and accessible way. Jung himself explains: The individual is the only reality. The further we move away from it, the more we approach mere collective abstraction.

For a deeper dive, The Undiscovered Self* (1957) is another excellent entry point, offering a concise yet powerful discussion on the conflict between the individual and modern society. Jung warns: “The bigger the crowd, the more negligible the individual becomes.”

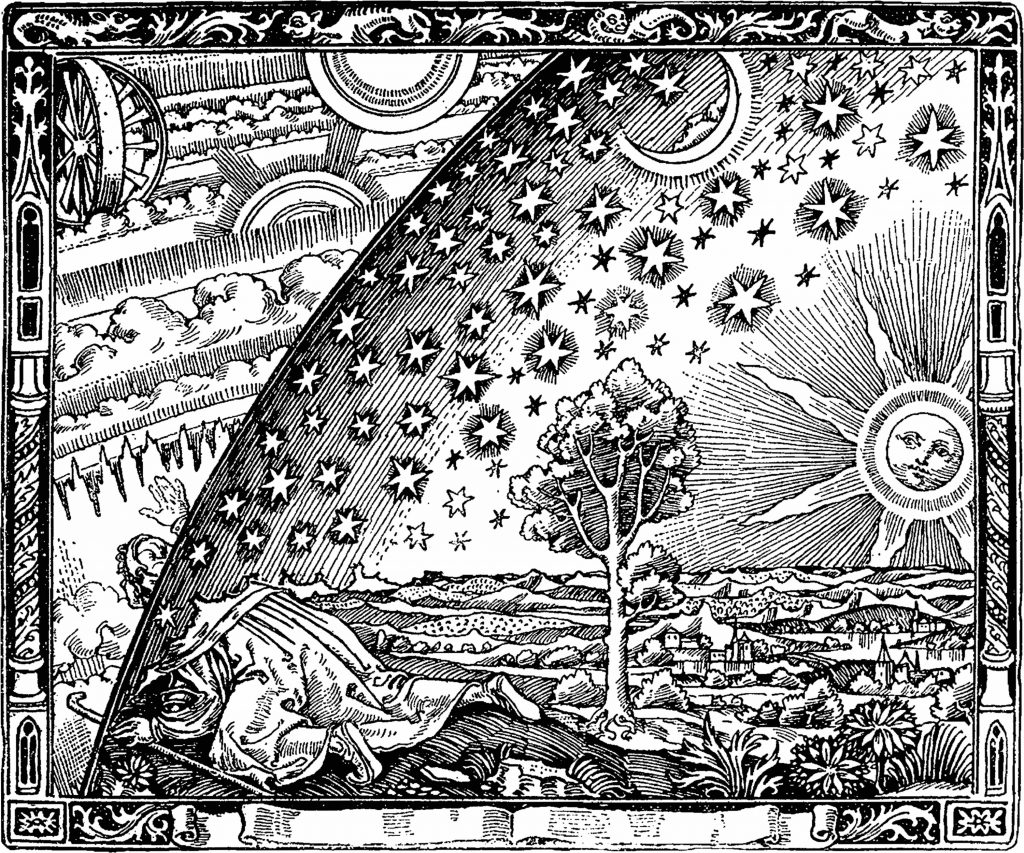

Those ready for more challenging material may explore Psychological Types* (1921), where Jung introduces his famous introversion-extraversion theory, or The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious* (1959), which delves into the symbolic structures shaping our inner world. However, these works require patience, as Jung’s writing can be intricate and metaphorical.

Ultimately, the best approach is to start with the accessible works and gradually build up to the more technical texts. As Jung himself said: “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

The Red Book (Liber Novus)*, published posthumously in 2009, is one of Jung’s most fascinating yet challenging works. Unlike his other books, which are structured as psychological treatises, The Red Book (Click here to read my own experiences with this book) is a deeply personal and visionary account of his own inner experiences during a period of intense psychological crisis. Filled with vivid imagery, dreamlike narratives, and symbolic encounters, it offers a rare glimpse into the foundations of his theories.

Jungian Analysis of Modern Political Tendencies: America, Ukraine, and Europe

In the lens of Jungian psychology, figures like Donald Trump can be viewed as embodiments of deep, collective emotional currents. Trump represents an archetypal “Trickster” figure—someone who channels the chaos and frustration of the collective unconscious, rather than leading with clear, rational goals. His populist rhetoric taps into a sense of collective anger, driven by perceptions of economic decline, global competition, and a fear of lost influence. This collective frustration manifests in simplistic solutions to complex geopolitical problems and a rhetoric that often bypasses facts in favor of emotionally charged slogans.

Trump’s approach to foreign policy aligns with a more isolationist, defensive posture, which Jung might interpret as the “King without a vision.” This archetype is not concerned with long-term strategies or alliances, but rather with consolidating power and pursuing short-term emotional satisfaction. Trump’s comments regarding abandoning Ukraine or reducing the role of the U.S. in global alliances reflect a retreat into the collective unconscious, where fear and anxiety about international entanglements outweigh the rational need for diplomacy and cooperation. This sentiment resonates with a larger portion of the American public who feel alienated by globalization and its perceived threats.

In Europe, this trend toward isolationism and retreat from collective international cooperation is also palpable. Nations are increasingly drawn toward nationalist movements that appeal to their unique cultural identities and fears about the future. Jung would likely argue that these nations are projecting their unconscious anxieties onto external “others,” which fuels the rise of populist leaders who promise to restore control and protect borders.

Ukraine, situated at the intersection of these shifting political forces, may be seen as caught between competing archetypal forces: the “Hero” striving for autonomy and freedom, and the “Shadow” embodying the fears and complexities of being caught in a geopolitical struggle between larger powers. The collective psyche of Ukraine reflects both hope for sovereignty and the deep psychological scars of historical domination, with the ongoing conflict becoming a symbolic battleground for the archetypes of independence and submission.

In conclusion, Jung would view these current political dynamics not just as tactical maneuvers but as expressions of underlying psychological processes. The rise of populist figures and movements across the globe represents an amplification of collective fears and frustrations. These movements tap into the deeper, often unconscious, emotional currents of entire populations, directing those energies toward political action. Jung might warn that this unconscious mobilization of collective forces—if unchecked—could have dangerous and far-reaching consequences for global stability.

*affiliate link

Literature

Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his symbols. Aldus Books.

Jung, C. G. (1957). The undiscovered self. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1921). Psychological types (H. G. Baynes, Trans.). Routledge. (Original work published 1921)

Jung, C. G. (1959). The archetypes and the collective unconscious. Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (2009). The red book: Liber novus (M. A. Edwards, Trans.). W. W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 2009)

Our Current Courses (Click to find out More)

Sign up for our free e-book: 10 easy ways to instantly improve your dream memory