Today’s Guest Blog: ‘Trickster Archetype’ is written by Christian Gerike M.A, teaching assistant in the Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, Psychology Department, for the Introduction to Psychology and Myth, Dream, and Symbol courses. Christian has also two other guest blogs for Mindfunda: How to Remember your Dreams, (Click to read more) and Sleeping well, Remembering Dreams.(Click to read more)You can read more about the Trickster on Mindfunda in Trickster Gods: Tricky ways to discover the Self,(Click to read more) and Trickster Tactics: from Archetype to Evolution(Click to read more).

Today’s Guest Blog: ‘Trickster Archetype’ is written by Christian Gerike M.A, teaching assistant in the Sonoma State University, Rohnert Park, California, Psychology Department, for the Introduction to Psychology and Myth, Dream, and Symbol courses. Christian has also two other guest blogs for Mindfunda: How to Remember your Dreams, (Click to read more) and Sleeping well, Remembering Dreams.(Click to read more)You can read more about the Trickster on Mindfunda in Trickster Gods: Tricky ways to discover the Self,(Click to read more) and Trickster Tactics: from Archetype to Evolution(Click to read more).

Trickster Archetype

The whimsical and diabolical Trickster is a character found in folk tales and myths around the world.

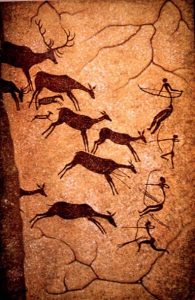

The Trickster, generally recognized as one of the oldest expressions of mankind, originated in and is the chief mythological character of the paleolithic world.

Found among the simplest to the most complex of indigenous groups, this is a figure and a theme with “. . . a special and permanent appeal and an unusual attraction for mankind from the very beginnings of civilization” (Radin, 1956, p. xxiii).

The Trickster is a strange combination of benevolence, harmless mischief, and destructive malice.

Erdoes and Ortiz, in their 1998 book American Indian Trickster Tales, (Click to buy the book and support Mindfunda) describe the Trickster as:

“. . . always hungry for another meal swiped from someone else’s kitchen, always ready to lure someone else’s wife to bed, always trying to get something for nothing, shifting shapes (and even sex), getting caught in the act, ever scheming, never remorseful” (p. xiii).

In West Africa we find the Spider, the Tortoise in Nigeria, the Hare among the Bantu people, in Hawaii is the Trickster/Culture Hero Maui, in ancient Greece is androgynous Hermes/Mercury, in Scandinavia shape-shifter Loki lies and steals from the other gods, in Europe is Reynard the Fox, on the Andaman Islands is the Kingfisher, in Turkey it is Nasr-eddin, the hodja (clown-priest).

In traditional and modern Native American cultures, there is Raven in the Pacific Northwest, androgynous and shape-shifting Coyote in California, the Great Hare among northern and eastern woodland tribes, and in the southwest the Hopi have Keshari, the Clown. In looking at Native American traditions we see Coyote the Trickster par excellence.

Trickster Archetype Defined

Trickster is proud to be described as destructive, immature, devious, quick-witted, sly, deceiving, lying, thieving, villainous, cowardly, mischievous, shrewd, cunning, wise, self-centered, ingenious, ambiguous, bi-sexual, fool, lecher, and a cheat.

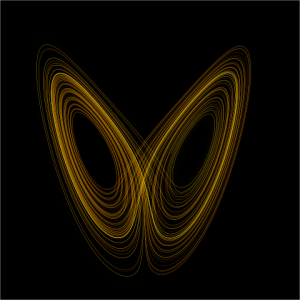

By User:Wikimol, User:Dschwen – Own work based on images

“Clever and foolish at the same time, smart-asses who outsmart themselves” (Erdoes & Ortiz, 1998, p xiv Click to buy the book and support Mindfunda). It is this aspect of the Trickster that has made him such an entertaining character around the world. In manifesting these characteristics, the Trickster represents the chaos principal, the principle of disorder.

Trickster Archetype: Dark vs Light

Jung (1956/1969) sees the dark side of the Trickster as being “. . . a collective shadow figure, a summation of all the inferior traits of characters in individuals . . . subhuman and superhuman, a bestial and divine being, whose chief and most alarming characteristic is his unconscious.” A ‘cosmic’ being of divine-animal nature, superior to man because of his superhuman qualities; inferior to him because of his reason and unconsciousness (pp. 270, 263, 264).

There is another side to the Trickster. As the giver of all great boons—the fire-bringer, teacher of mankind—it is common for the Trickster to be a creator figure who created the earth and brings culture and civilization to humans.

In his role of bringing inventions, agriculture, tools, and fire the Trickster is a cultural hero. For example, the Japanese storm god Susanoo provided humankind with such necessities of life as daylight, fire, and water.

Among the Classical Greeks, Prometheus as creator brought into being all of the world’s animals;

Jan Cossiers

he brought fire, numbers, writing, farming, medicine, divination, metallurgy, and served as protector of humans.

Ikotomi the Spider, the Trickster of the Lakota and Dakota Sioux tribes, created time and space, invented language, gave the animals their names, and, as a prophet, foretold the coming of the white man.

We should keep in mind that since these contributions were bestowed upon humanity by Trickster, that there might be a Shadow side to these advances in civilization.

Trickster Archetype: Time

The Trickster is alive and well in mythic time – an era when the world and its inhabitants were very different from they are now, a time when there were animals that walked and talked as human beings do; and Trickster lurks about in historical time, when the earth is no different than today, though there may still be mythical lands where mythical beings interact with humans.

©2014-2017 oreocactus

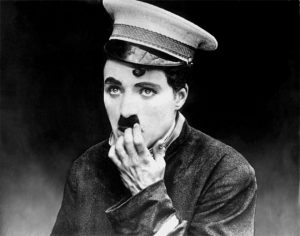

Even in modern times the Trickster abounds, as wide ranging as Charlie Chaplin, Wile E. Coyote, Richard Nixon, and the 3 Stooges.

Trickster Archetype: Gender

The trickster is usually male. Lewis Hyde, in his 1998 book, Trickster Makes This World: Mischief, Myth, and Art (Click to buy the book and support Mindfunda) explains that

- Tricksters may belong to patriarchal mythologies, ones in which the prime actors, even oppositional actors, are male.

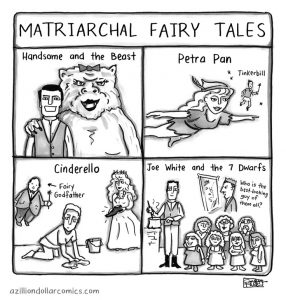

Cartoon: Azilliondollarcomicsdotcom - There may be a problem with the standard itself; female tricksters may simply have been ignored.

Morgan le Fay, female Trickster?

Art by Sandys, Frederick - Perhaps the trickster stories articulate some distinction between men and women and even in a matriarchal setting this figure would be male. (p. 336)

Trickster Archetype: Native North America

Trickster, in its earliest form among North American Indians, is at one and the same time creator and destroyer, giver and negator, he who dupes others and who is always duped himself.

He behaves as he does from impulses over which he has no control, possessing no values, moral or social, he is at the mercy of his passions and appetites. The others in Trickster stories possess similar traits: the animals, the various supernatural beings and monsters, and man.

Paul Radin, in The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology, (Click to buy the book and support Mindfunda), tells us that:

The overwhelming majority of all so-called trickster myths in North America give an account of the creation of the earth, or at least transforming of the world, and have a hero who is always wandering, who is always hungry, who is not guided by normal conceptions of good or evil, who is either playing tricks on people or having them played on him and who is highly sexed.

Almost everywhere he has some divine traits. These vary from tribe to tribe. In some instances he is regarded as an actual deity, in others as intimately connected with deities, in still others he is at best a generalized animal or human being subject to death. (1956, p. 155)

Trickster Archetype: Coyote

While appearing both in human and animal forms in Native North America, Trickster is generally an animal with human characteristics, such as the hare, raven, spider.

It is Coyote, however, who is the classic Trickster in the Native American myths of North America, if not worldwide. Barry Lopez (1977, p. xv), informs us that

No other personality is as old, as well known, or as widely distributed among the tribes as Coyote. He was the figure of paleolithic legend among primitive peoples the world over, and though he survives today in Eurasian and African folktales, it is among native Americans, perhaps, that his character achieves its fullest dimension.

Kimberly A. Christen (1998), in Clowns & Tricksters: An Encyclopedia of Tradition and Cultures, describes Coyote as being most recognizable by his flaws: selfish, disrespectful, glutton, at worst a murder and thief.

“The coyote shares with other tricksters a total disregard for cultural mores and laws. In order to teach young people the proper way to act, stories about the coyote often focus on greed and wrongheadedness” (p. 33). We can see Coyote at his finest among the Lakota:

“The Lakota coyote Mica has an unending sexual appetite, he steals, and he is greedy and generally disrespectful. Mica disregards all social mores by being selfish and rude. Mica takes advantage of his friends’ wives, he steals food from his neighbors, and he lies to get whatever he wants, never working at all. Mica outwits other people using lies, tricks, and any other means possible. He challenges people, animals, and other powerful beings to contests he is sure to win; if necessary he cheats to make sure he will be victorious. (Christen, 1998, pp. 32-33)

Trickster Archetype: Its Function

The animal aspect of the Trickster indicates a close identification with nature. Howard Norman describes the Trickster’s role in explicating the relationship of humans and the natural world:

“These tales enlighten an audience about the sacredness of life. In the naturalness of their form, they turn away from forced conclusions, they animate and enact, they shape and reshape the world” (as quoted by Erdoes & Ortiz, 1998, p. xix).

Barry Lopez (1977, pp. xvi-xvii), in Giving Birth to Thunder, Sleeping with his Daughter: Coyote Builds North America, (Click to buy the book and support Mindfunda) presents several of the Trickster’s social and psychological roles.

Lopez states that while “Coyote stories were told all over north America . . . with much laughter and guffawing and with exclamations of surprise and awe . . . the storytelling was never simply just a way to pass time.” Coyote stories

- Detailed tribal origins;

- emphasized a world view thought to be a correct one;

- dramatized the value of proper behavior;

- participating in the stories by listening to them renewed one’s sense of tribal identity;

- the stories were a reminder of the right way to do things—so often, of course, not Coyote’s way;

- telling Coyote stories relieved social tensions. Listeners could release anxieties through laughter, vicariously enjoying Coyote’s proscribed and irreverent behavior; and

- Coyote’s antics thus compare with the deliberately profane behavior of Indian clowns in certain religious ceremonies. In a healthy social order, the irreverence of both clown and Coyote only serve, by contrast, to reinforce the existent moral structure.

With the Trickster we experience paradoxes, if not outright contradictions, of being human. “Coyote, part human and part animal, taking whichever shape he pleases, combines in his nature the sacredness and sinfulness, grand gestures and pettiness, strength and weakness, joy and misery, heroism and cowardice that together form the human character” (Erdoes & Ortiz, 1998, p. xiv).

It is in the Trickster these combinations of qualities are recognized as being in the world, and from the Trickster we learn existential lessons as to the consequences of letting our darker side rule our lives.

Through the Trickster we can see that “Individuals have the power to recognize their shadows and in doing so, choose the better part” (Lundquist, 1991, p. 29).

Conclusion

Jung (1956/1969) sees the Trickster as “. . . simply the reflection of an earlier, rudimentary stage of consciousness . . .” (p. 261).

The Trickster symbol, however is not static and changes through time, with Coyote now right alongside Charlie Chaplin.

The Trickster lets us know that there is no clear differentiation of the divine and the ordinary; that, in fact, the divine can have less than stellar qualities.

Paul Radin (1956) concludes that the Trickster

. . . became and remained everything to every man—god, animal, human being, hero, buffoon, he who was before good and evil, denier, affirmer, destroyer and creator. If we laugh at him, he grins at us. What happens to him happens to us. (p. 169)

The Trickster carries an enormous number of opposites and many of the adventures could be seen as arising from the tension that is found between these opposites.

Trickster dwells in the realm of the Shadow, but perhaps that is for our salvation. C.G. Jung (1956/1969), at the end of his essay On the Psychology of the Trickster-figure, states:

“As in its collective mythological form, so also the individual shadow contains within it the seed of an enantiodromia, of a conversion into its opposite” (p. 272). Let the Trickster inhabit the darker side of life, while we use that force, through his stories, to bring us to the good side of life. Let us have balance by leaving evil in the realm of the gods and keeping good in the realm of humanity.

Bibliography

Bastian, D.E. & Mitchell, J.K. (2004), Handbook of Native American mythology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bierhorst, J, (1985). The mythology of North America. New York, NY: William Morrow.

Bright, W. (1993). A Coyote reader. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Campbell, J. (1969). The masks of god: Primitive mythology. New York, NY: Penguin Compass.

Christen, K. A. (1998). Clowns & tricksters: An encyclopedia of tradition and culture. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Erdoes, R. & Ortiz, A. (Eds.). (1998). American Indian trickster tales. New York, NY: Viking.

Hyde, L. (1998). Trickster makes this world: Mischief, myth and art. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Jung, C. G. (1969). On the psychology of the trickster figure. In Read, H., Fordham, M., Adler, G., & McGuire, W. (Eds.) (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.), The collected works of C. G. Jung: Vol. 9, part 1. The archetype and the collective unconscious (2nd ed., pp. 255-272). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1956)

Kirk, G.S. (1970). Myth: Its meaning & functions in ancient & other cultures. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Laffert, J.V. (Ed.) (2008). Essential visual history of world mythology. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society.

Leeming, D.A. (1990). The world of mythology: An anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Lopez, B. (1977). Giving birth to Thunder, sleeping with his daughter: Coyote builds America. New York, NY: Avon Books.

Lundquist, S. E. (1991). The Trickster: A transformation archetype. Distinguished Dissertations Series 11. San Francisco, CA: Mellen Research University Press.

Radin, P. (1956). The Trickster: A study in American Indian mythology. New York, NY: Schocken Books.

Shipley, W. (Ed., Trans). (1991). The Maidu Indian myths and stories of Hanc’ibyjim. Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books.

Vizenor, G. (1993). Trickster discourse: Comic and tragic themes in native American literature. In Lindquist, M.A. & Zanger, M. (Eds.), Buried roots and indestructible seeds: The survival of American Indian life in story, history, and spirit (pp. 67-83). Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press.

Our Current Courses (Click to find out More)

Sign up for our free e-book: 10 easy ways to instantly improve your dream memory